Genes load the gun, exposures pull the trigger.

What You'll Learn on This Page

This page is designed as a primer for clinicians, researchers, and the science-minded, whether you're here to advance your practice, explore a new framework for understanding chronic disease, or because a patient pointed you in our direction. Here's what it will cover:

- What is the exposome? — the scientific framework for understanding how environmental, lifestyle, and medical exposures drive chronic disease

- How exposures cause disease. — mechanisms including gene-environment interactions, epigenetics, and critical windows of susceptibility

- What contributes to a patient's exposome. — environmental, humanistic, and iatrogenic factors, with some examples

- The exposome in autoimmunity. — an example of how exposures trigger and exacerbate conditions like Hashimoto's thyroiditis

- Why traditional approaches fall short. — and how EXPIN's personalized exposure-outcome mapping differs from working with taking labs and querying AI tools.

- Clinical utility of the patient expotype. — how clinicians can use exposome insights to guide treatment, testing, and patient empowerment

What is the exposome?

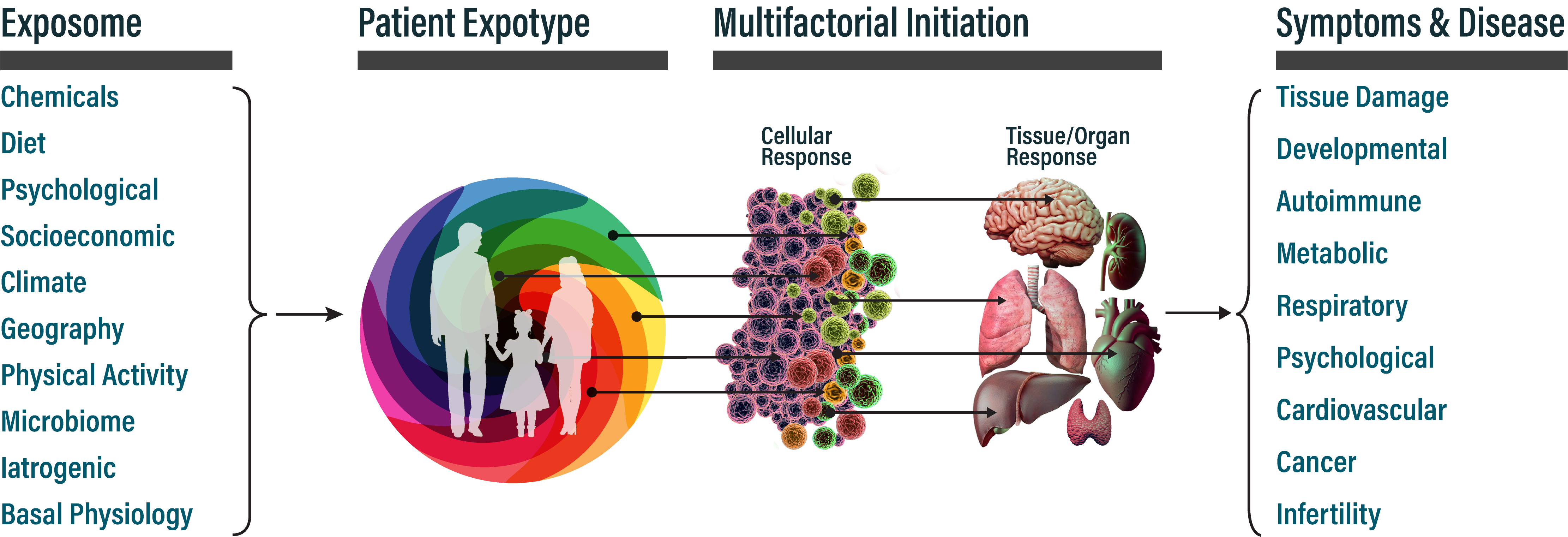

Following the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2001, scientists realized that chronic diseases were more than just the consequence of "bad genes." They are also the result of an individual's environmental exposures.1 In fact, >70% of all chronic diseases can be linked to environmental factors.2 For most patients with chronic disease, the majority of their disease risk lies outside their DNA and is potentially modifiable.

To address this disparity between genes and the environment, in 2005, Dr. Christopher Paul Wild, then Director of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (World Health Organization), coined the term "exposome."3 Dr. Wild defined the exposome as a person's accumulated environmental exposures from conception onwards.

In the two decades since, large-scale cohort studies, advances in biomonitoring, and computational methods have matured exposomics from concept to actionable science. Recognizing that the majority of chronic disease is affected by the exposome, in 2025 a multidisciplinary group of scientists convened at the Banbury Exposomics Consortium4 to propose a formal definition of the exposome and its study "exposomics," identify key challenges, and promote its adoption in biomedicine. They defined the exposome as the integrated compilation of all physical, chemical, biological and (psycho)social influences that "impact biology."5

Exposomics draws on molecular biophysics, toxicology, epidemiology, clinical medicine, and data science to connect exposures to health outcomes. Despite accounting for the majority of disease burden, exposome research has received a fraction of the investment directed toward genomics, creating both a gap and an opportunity that The Exposome Intelligence Company (EXPIN) aims to address, working with international partners in academia and governments alike.

How exposures cause disease.

Understanding how exposures translate into disease is essential for clinical interpretation. Causation is rarely linear: most chronic diseases arise from multiple exposures acting in concert, modulated by genetic susceptibility and timing. The same clinical outcome can result from different exposure combinations, and the same exposure can contribute to different diseases depending on context. Key mechanisms include:

Gene-Environment Interaction

Genetic variants modulate individual susceptibility to exposures. Polymorphisms in detoxification genes (e.g., GST, CYP450 families) and immune genes (e.g., HLA haplotypes) can amplify or attenuate the effects of specific exposures. Two individuals with identical exposures may have vastly different outcomes based on their genetic background.

Epigenetic Modification

Exposures can alter gene expression without changing DNA sequence. Environmental chemicals, stress, and nutritional factors affect DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA expression. These epigenetic modifications can persist for years and, in some cases, transmit across generations.

Critical Windows of Susceptibility

The timing of exposure matters. Fetal development, early childhood, puberty, and perimenopause represent periods of heightened vulnerability when exposures can have outsized effects on disease trajectory. Exposures during these windows may not manifest as disease for decades.

Dose-Response and Latency

Chronic low-dose exposures can accumulate over time. Many exposure-disease relationships involve long latency periods: symptoms may appear years or decades after the relevant exposures occurred. This temporal disconnect makes exposure identification challenging without systematic assessments.

Bioaccumulation and Body Burden

Lipophilic compounds (e.g., PCBs, PBDEs, dioxins) accumulate in adipose tissue and can have half-lives measured in years. Total body burden reflects cumulative lifetime exposure, not just recent contact. Mobilization during weight loss, illness, or lactation can release stored toxicants.

What contributes to a patient's exposome.

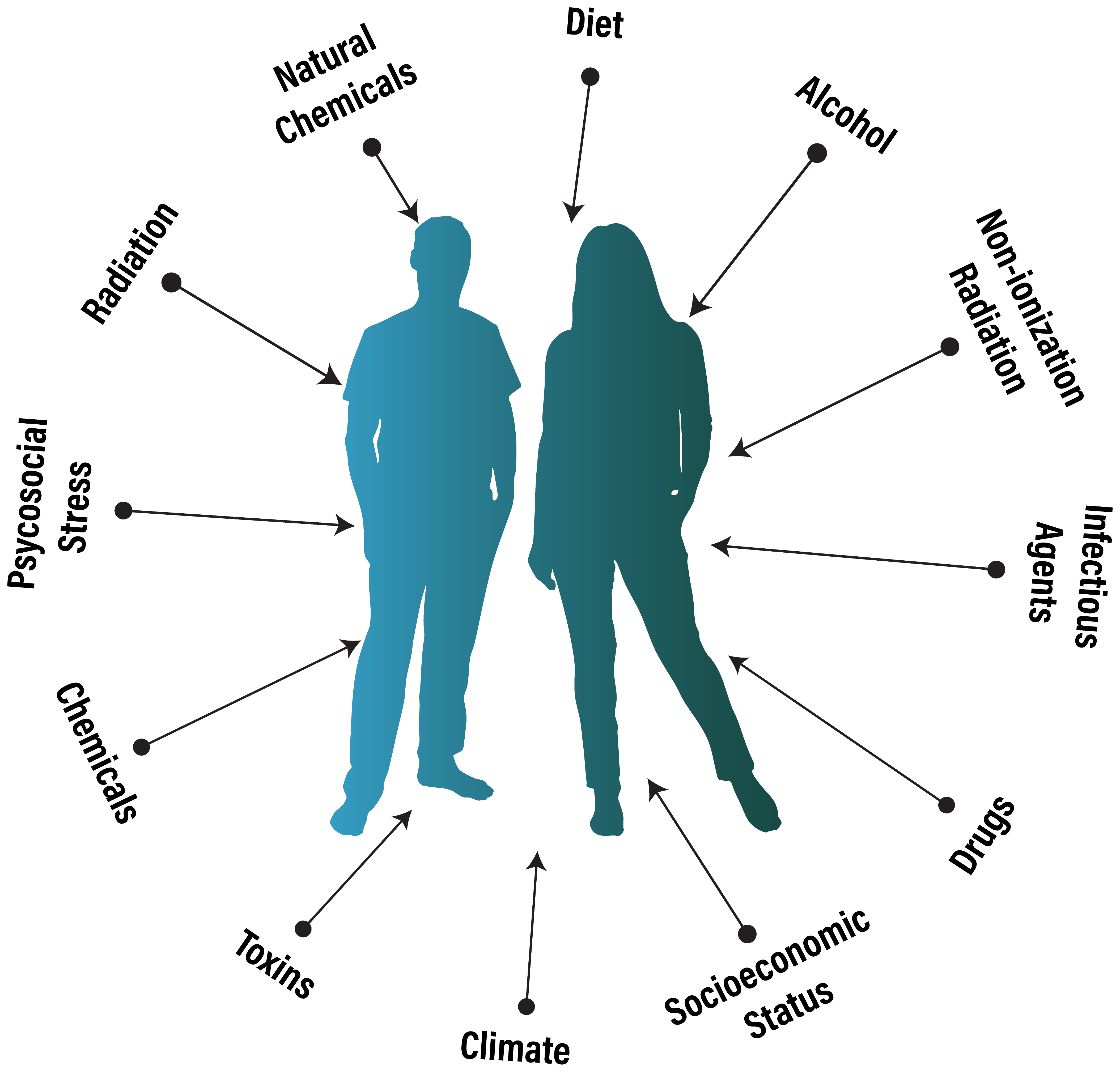

A patient's exposome can be divided into three broad domains:6-13

Environmental — external agents that enter or impact the body, including:

- Chemical: industrial pollutants, pesticides, heavy metals, solvents, air and water contaminants

- Physical: radiation (UV, ionizing), noise, temperature extremes, electromagnetic fields

- Biological: infectious agents (viral, bacterial, parasitic), microbiome perturbations, allergens

Humanistic — factors shaped by behavior, circumstance, and internal state, including:

- Behavioral: diet, physical activity, sleep patterns, substance use

- Psychosocial: chronic stress, trauma, social isolation

- Socioeconomic: occupation, housing quality, healthcare access, education

Iatrogenic — exposures arising from medical care, including:

- Pharmacological: prescription drugs, OTC medications, polypharmacy interactions

- Procedural: medical radiation (CT, fluoroscopy), surgical implants, anesthesia

- Interventional: chemotherapy, immunosuppressants, checkpoint inhibitors, hormone therapies

Across these three domains, an individual patient's exposome may encompass thousands of distinct factors, each with the potential to contribute to adverse health outcomes depending on dose, timing, duration, and genetic susceptibility. The exposome also includes absences (i.e. nutrient deficiencies, inadequate sleep, insufficient sunlight), which can be as consequential as toxic exposures. Cataloging and quantifying these factors remains the central challenge in integrating exposomics with biomedicine.

Among environmental exposures, chemical agents have received the most research attention.7 Blood and urine biomonitoring reveals dozens to hundreds of anthropogenic chemicals in individual exposomes, many linked to human diseases.8 To add color, these include, but are not limited to:

| Chemical Class | Example | Human Toxicity* |

|---|---|---|

| Brominated flame retardants | Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) | Endocrine Disruption, Carcinogen |

| Dioxins | Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) | Chloracne, Carcinogen |

| Drugs (Prescription and OTC) | Acetaminophen, opioids | — |

| Metals | Mercury, cadmium | Neurotoxicity, Carcinogen |

| Musk Compounds | Musk ambrette | Skin Allergen |

| Nanomaterials | Fullerenes | Pulmonary Toxicity |

| Perfluorinated compounds (PFAS) | PFOS, PFOA | Endocrine Disruption |

| Pesticides | Dieldrin | Developmental Neurotoxicity |

| Phenols | Bisphenol A (BPA) | Endocrine Disruption, Neurotoxicity |

| Phthalates | Diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) | Endocrine Disruption |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | 2,3'-Dichlorbiphenyl | Renal And Hepatotoxicity |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | Benzo(a)pyrene | Carcinogen |

* This is not an inclusive list of human toxicities associated with these chemical classes.

Exposure does not guarantee harm. Humans have evolved robust defense systems: Phase I/II detoxification enzymes, antioxidant pathways, metal-chelating proteins, and DNA repair mechanisms that handle tens of thousands of lesions daily.14,15

This is what makes systematic exposure assessment clinically valuable: identifying which factors, in which patients, may have overwhelmed normal protective mechanisms.

The exposome in autoimmunity.

Autoimmune diseases exemplify the gene-exposure interaction model. The prevailing framework is that genetic susceptibility (the "loaded gun") combines with environmental triggers (the "pulled trigger") to initiate loss of immune tolerance.

The Triggering Model

Autoimmunity rarely arises from genetics alone. Concordance rates in identical twins for most autoimmune conditions are 12-70%, suggesting that non-genetic factors account for the majority of disease risk. Exposures can trigger autoimmunity through molecular mimicry, bystander activation, epitope spreading, and direct tissue damage.

Hashimoto's Thyroiditis: Autoimmunity Case Study

Hashimoto's disease illustrates how the exposome converges on a single target organ, including but not limited to:

- Iodine: Both deficiency and excess are associated with thyroid autoimmunity in nuanced manner. Rapid iodine repletion in deficient populations increases Hashimoto's incidence.

- Selenium deficiency: Reduces antioxidant capacity in thyroid tissue; supplementation may lower antibody titers in some patients.

- Thyroid-disrupting chemicals: PCBs, PBDEs, perchlorates, and phthalates interfere with thyroid hormone synthesis, transport, and receptor binding.

- Infections: Yersinia enterocolitica shares antigenic epitopes with thyroid tissue. EBV, Hepatitis C, and H. pylori have also been implicated.

- Stress and trauma: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and elevated cortisol alter immune function and may precipitate or exacerbate autoimmune flares.

Similar exposure-trigger patterns appear across autoimmune conditions: silica and solvents in systemic sclerosis, smoking in rheumatoid arthritis, EBV in multiple sclerosis, and gluten in celiac disease. Systematic exposome assessment can identify modifiable factors regardless of the specific diagnosis by uncovering probable exposures; their source, combination, accumulation, and latency of effect; and their relevance to a patient's genetic susceptibility.

Why traditional approaches fall short.

Clinicians have two primary methods for assessing a patient's exposome: biomonitoring and questionnaires. Neither is sufficient.

Biomonitoring (blood, urine, hair analysis) provides objective data but suffers from significant constraints. Comprehensive panels cost thousands of dollars. Most tests capture only recent exposures, missing historical burden that may have triggered disease years or decades prior. No single panel covers more than a fraction of relevant compounds. And results require specialized interpretation most clinicians lack training to provide.

Questionnaires capture history but introduce different problems. Recall bias limits accuracy, especially for exposures decades prior. Patients don't know what they don't know—they can't report contaminated water supplies they were never informed about or workplace chemicals they were never told were hazardous. No standardized instrument captures all domains. And thorough exposure histories require one to two hours of expert interview time that few clinical settings can accommodate.

The result: clinicians treating chronic disease patients have no practical way to systematically assess the exposome. Treatable root causes go unidentified because they were never asked about or measured.

The AI Mirage

Modern AI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and clinical platforms like OpenEvidence have lowered the barrier to exploring exposure-disease relationships. But they introduce serious risks that make them unsuitable for clinical exposome assessment:

- Population-level retrieval, not personalized synthesis: Generic AI returns what's statistically associated in the literature. It cannot tell a specific patient which of their exposures; given their timing, duration, co-exposures, and genetic background; are most likely contributing to their condition.

- Point-source search, not integration: These tools find information. They do not integrate it into a coherent, weighted, actionable assessment of individual risk. They are search engines, not clinical reasoning systems.

- Hallucination: Large language models confidently generate plausible-sounding but fabricated associations. A patient may receive authoritative-seeming information linking their condition to an exposure with no scientific basis or miss a well-established connection entirely. In medicine, confabulation can cause direct patient harm.

- No cumulative patient model: Each conversation starts fresh. These tools cannot build a persistent picture of an individual's exposure history, track changes over time, or synthesize patterns across sessions without deteriorating.

- Context window limits: Even within a single session, LLMs hold limited working memory. A comprehensive exposure history spanning residence, occupation, diet, medications, infections, trauma, and lifestyle across a lifetime quickly exceeds this capacity. Critical details relevant to the multifactorial nature of the exposome get dropped.

- No evidence weighting: A single case report is presented with the same confidence as a meta-analysis of 50 studies. Clinicians and patients cannot distinguish strong signals from noise.

Generic AI can surface relevant literature. It cannot replace systematic exposure assessment.

Clinical utility of the patient expotype.

The link between environmental exposures and disease is not new, from chimney sweeps' scrotal cancer (1775)16 to Roman lead poisoning17 to mercury-induced madness in hatters.18 Modern epidemiology has established causal links between smoking and COPD,19 asbestos and mesothelioma,20 and childhood lead exposure to cognitive impairment,21 with molecular mechanisms now well-defined.14

What's changed is scale: chronic disease accounts for 86% of U.S. healthcare costs, and half of American adults have at least one chronic condition.22,23 Most chronic diseases involve multiple exposures acting in concert: autoimmune conditions triggered by chemicals, infections, diet, and microbiome disruption;24 autism spectrum disorder linked to metals, pesticides, air pollutants, prenatal exposures, and even early media exposure.25 Disentangling these webs requires tools that can hold the full picture.

An expotype is a personalized map of a patient's exposome, a ranked assessment of which exposures in their history have documented associations with their symptoms or conditions. EXPIN generates expotypes by integrating AI-mediated patient interviews, geographic and environmental databases, toxicological resources (EPA, ATSDR), public health databases (EHR/claims data), and curated scientific literature qualified using IARC/WHO-inspired evidence standards.

With an expotype, clinicians can:

- Identify modifiable exposures that can be reduced or eliminated

- Prioritize functional testing based on individualized risk rather than shotgun protocols

- Contextualize unexplained findings by connecting symptoms to plausible upstream causes

- Guide treatment sequencing and justify clinical decisions with evidence-based rationale

- Reduce diagnostic uncertainty for patients dismissed or told "everything looks normal"

What EXPIN does not replace

EXPIN is an investigative tool, not a diagnostic system. It does not replace clinical judgment, laboratory confirmation, or the therapeutic relationship. The goal is to expand the clinician's lens and give patients agency in understanding their own health.

Exposome-informed medicine is still emerging. EXPIN is building toward a future where systematic exposure assessment becomes as routine as family history or medication reconciliation, a standard component of precision care for chronic and autoimmune disease.5

References

- Venter, J.C., et al. (2001) The sequence of the human genome. Science 291, 1304-1351.

- Rappaport, S.M. and Smith, M.T. (2010) Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science 330, 460-461.

- Wild, C.P. (2005) Complementing the genome with an "exposome": the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14, 1847-1850.

- Center for Innovative Exposomics (2026) Banbury Consortium. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/centers/center-innovative-exposomics/banbury-consortium.

- Miller, G.W. (2025) Integrating exposomics into biomedicine. Science 388, 356-358.

- Wei, X., et al. (2022) Charting the landscape of the environmental exposome. Imeta 1, e50.

- Beans, C. (2025) Exposome research comes of age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 122, e2535078122.

- Chen, Q., et al. (2021) Identifying active xenobiotics in humans by use of a suspect screening technique coupled with lipidomic analysis. Environ Int 157, 106844.

- Bogdanos, D.P., et al. (2013) Infectome: a platform to trace infectious triggers of autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 12, 726-740.

- Selman, C. (2024) The dietary exposome: a brief history of diet, longevity, and age-related health in rodents. Clin Sci (Lond) 138, 1343-1356.

- Rushing, B.R., et al. (2023) The Exposome and Nutritional Pharmacology and Toxicology: A New Application for Metabolomics. Exposome 3.

- Barouki, R. (2024) A toxicological perspective on climate change and the exposome. Front Public Health 12, 1361274.

- Kalter, H. (2000) Folic acid and human malformations: a summary and evaluation. Reprod Toxicol 14, 463-476.

- Klaassen, C.D. (2019) Casarett and Doull's toxicology: the basic science of poisons, Ninth edition. McGraw-Hill Education, New York.

- Schuch, A.P., et al. (2017) Sunlight damage to cellular DNA: Focus on oxidatively generated lesions. Free Radic Biol Med 107, 110-124.

- Azike, J.E. (2009) A review of the history, epidemiology and treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum. Rare Tumors 1, e17.

- Gilfillan, S.C. (1965) Lead poisoning and the fall of Rome. J Occup Med 7, 53-60.

- Buckell, M., et al. (1993) Chronic mercury poisoning. 1946. Br J Ind Med 50, 97-106.

- Forey, B.A., et al. (2011) Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating smoking to COPD, chronic bronchitis and emphysema. BMC Pulm Med 11, 36.

- Orenstein, M.R. and Schenker, M.B. (2000) Environmental asbestos exposure and mesothelioma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 6, 371-377.

- Koller, K., et al. (2004) Recent developments in low-level lead exposure and intellectual impairment in children. Environ Health Perspect 112, 987-994.

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2023) National Health Statistics Report. CDC.

- National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. (2019) CDC.

- Touil, H., et al. (2023) Differential impact of environmental factors on systemic and localized autoimmunity. Front Immunol 14, 1147447.

- Christakis, D.A. (2020) Early Media Exposure and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Heat and Light. JAMA Pediatr 174, 640-641.